We've already provided a brief

description of the solar system as

it relates to eclipses — in other words, the relationships of

the Sun, Moon, and Earth.

However, there's much more to the solar system than that; in particular,

its amazing scale is quite staggering. If you're interested in this,

read on; in this page, we will attempt to explain the shape of the solar

system in more detail, and even try to give an idea of its scale.

The Problem of Scale

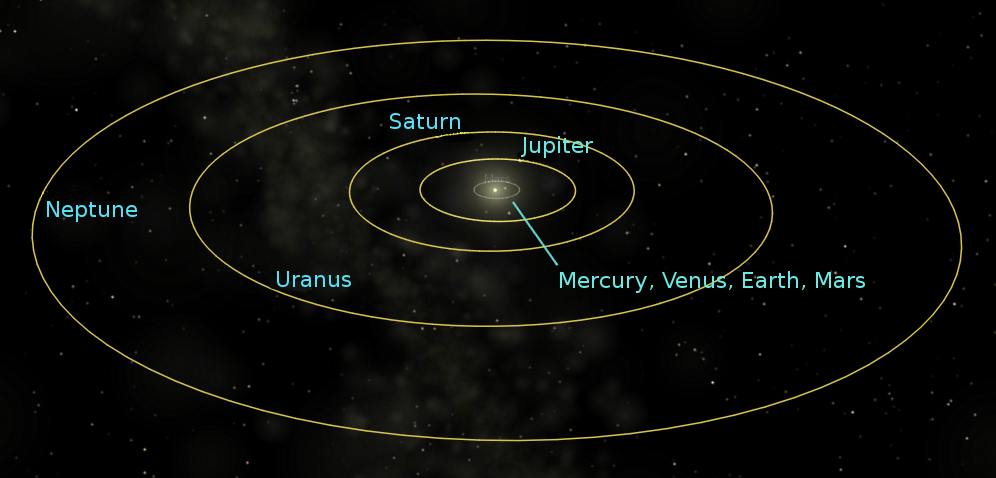

This might seem like a simple thing to explain: let's just see

a diagram of the solar system. OK, here you go!

This diagram shows the Sun and the eight planets we know of. But as

you can see, it's not very satisfactory, for a few reasons.

First, Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars are missing! Well, actually,

they're there, they're just far too small to be seen. In fact, even

their orbits are too small to be seen on this scale: they're lost in the

glare around the Sun. (If you look really closely, you can just see

Mars' orbit.)

Second, even the big planets are too small to be seen. Jupiter, which

is the largest of all the planets, would be just over a hundredth of a

pixel wide at this scale. The Sun itself would be just over a tenth of

a pixel, and Earth would be a little over a thousandth of a pixel.

Then there are quite a lot of missing objects. You

might notice that Pluto is missing, but if that's a concern, it's only

because Pluto is very well known. In reality, Pluto is just one of many

similar dwarf planets, and they're all missing from this diagram. If Pluto

should be there, then so should

ErisEris (dwarf planet)

An article on the dwarf planet Eris, which orbits the Sun beyond Neptune. (Wikipedia)

,

HaumeaHaumea

An article on the dwarf planet Haumea, which orbits the Sun beyond Neptune. (Wikipedia)

,

Gonggong(225088) Gonggong

An article on the trans-Neptunian object Gonggong (formerly 2007 OR10), which is probably a dwarf planet. (Wikipedia)

,

MakemakeMakemake

An article on the dwarf planet Makemake, which orbits the Sun beyond Neptune. (Wikipedia)

,

Quaoar50000 Quaoar

An article on the trans-Neptunian object Quaoar, which orbits the Sun beyond Neptune. (Wikipedia)

,

Sedna90377 Sedna

An article on the trans-Neptunian object Sedna, which orbits the Sun far beyond Neptune. (Wikipedia)

, and

CeresCeres (dwarf planet)

An article on the dwarf planet Ceres, the largest object in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. (Wikipedia)

, at

least; but in reality, there are probably hundreds of dwarf planets

lurking in the farther reaches of the solar system.

Which brings us to the biggest problem — this diagram only

shows about half of a thousandth of the width of the solar system! The

overwhelming majority of our solar system is completely unknown and

unexplored, and its vast scale makes any realistic diagram of it basically

impossible. If we made a map of the whole solar system which was a

kilometre across, the Earth would be less than a thousandth of a

millimetre — about the size of a small bacterium.

Given this outrageous scale, it's quite hard to explain exactly how

all the pieces of our celestial home turf relate to each other. Nevertheless,

we're going to have a go. The simplest and most basic

part of the picture is the Sun and known planets, so let's start there.

The Sun and Planets

The Sun absolutely dominates our solar

system, containing over 99.8% of its total mass; so it is the immovable

anchor around which everything else orbits.

| Object |

Diameter |

Distance from Sun |

| (km) |

(million km) |

(AU) |

|

The SunSun

An article on the Sun. (Wikipedia)

|

1,392,000 |

0 |

0 |

|

MercuryMercury (planet)

An article on Mercury, the planet in our solar system closest to the Sun. (Wikipedia)

|

4,879 |

57.91 |

0.39 |

|

VenusVenus

An article on Venus, the second planet from the Sun in our solar system, and the planet closest to Earth in size. (Wikipedia)

|

12,104 |

108.2 |

0.72 |

|

EarthEarth

An article on our home planet, the Earth. (Wikipedia)

|

12,742 |

149.6 |

1.00 |

|

MarsMars

An article on Mars, the fourth planet from the Sun. (Wikipedia)

|

6,779 |

227.9 |

1.52 |

|

JupiterJupiter

An article on Jupiter, the fifth planet from the Sun, and the largest planet in our solar system. (Wikipedia)

|

139,822 |

778.6 |

5.20 |

|

SaturnSaturn

An article on Saturn, the giant ringed planet, and the sixth planet from the Sun. (Wikipedia)

|

116,464 |

1,433.5 |

9.58 |

|

UranusUranus

An article on Uranus, the seventh planet from the Sun. (Wikipedia)

|

50,724 |

2,875.0 |

19.2 |

|

NeptuneNeptune

An article on Neptune, the eighth planet from the Sun, and the outermost planet that we know of in our solar system. (Wikipedia)

|

49,244 |

4,504.4 |

30.1 |

The best-known things orbiting the Sun are, of course, the planets.

There are eight planets we know of, and they are all well within the

innermost reaches of the solar system. One reason for this is that we

don't yet have the ability to see planets orbiting farther out, even in

our own solar system; so

there could be others out therePlanet Nine

An article on Planet Nine, a hypothetical large planet in the outer region of the Solar System. (Wikipedia)

.

But we can at least list the ones we know about.

Looking at the numbers, you can see that the planets divide roughly into

2 groups: the 4 inner, terrestrial, planets, are all small (between

4,800 and 12,800 km in diameter) and quite close to the Sun (within

1.5 AU); the 4 outer, giant, planets, are all large (over 49,000 km),

and quite far from the Sun, extending out to 30 AU, 20 times farther than

the inner planets.

Of course, there's much more going on here than just the planets.

Most notable is the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, about

2–4 AU from the Sun; within this,

CeresCeres (dwarf planet)

An article on the dwarf planet Ceres, the largest object in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. (Wikipedia)

, the

largest asteroid and also a dwarf planet, orbits at about 2.8 AU.

And then there are the moons; the planets have numerous moons between them,

and some of these are very significant. Jupiter's moon Ganymede, and

Saturn's moon Titan, are both larger than Mercury; and there are seven

moons — including Earth's — which are larger than Pluto.

But there's a lot more to discover farther out, as well. Even at

the orbit of Neptune,

we have 2,000 times farther to go to get to the edge of the solar system.

Beyond Neptune

There is an immense amount of space in our solar system beyond the known

planets, and there is a lot happening there. However, we don't know

a lot about it, because out there, the light from the Sun is so faint

that any objects — even large planets — would be

so dim that they would be extremely hard to detect. Still, there are

some things we know, and some things about which we have strong

circumstantial evidence.

The first of the things we know about, just beyond Neptune, is

the Kuiper Belt. This is a belt of icy objects, similar to the asteroid

belt, and extending from about 30 to 50 AU from the Sun. There is a wide

range of sizes of objects in the Kuiper Belt, from grains of ice up to

dwarf planets; some of the larger ones

are PlutoPluto

An article on Pluto, formerly classified as a planet, but now known to be just one of many dwarf planets orbiting the Sun beyond Neptune. (Wikipedia)

,

MakemakeMakemake

An article on the dwarf planet Makemake, which orbits the Sun beyond Neptune. (Wikipedia)

,

HaumeaHaumea

An article on the dwarf planet Haumea, which orbits the Sun beyond Neptune. (Wikipedia)

,

Quaoar50000 Quaoar

An article on the trans-Neptunian object Quaoar, which orbits the Sun beyond Neptune. (Wikipedia)

, and

Varuna20000 Varuna

An article on the trans-Neptunian object Varuna, which orbits the Sun beyond Neptune. (Wikipedia)

.

The Scattered Disc is a wider belt of objects with more eccentric orbits,

and may be the source of short-period comets. It overlaps the Kuiper Belt,

but extends outwards possibly as far as 150 AU. The largest known

Scattered Disc object is ErisEris (dwarf planet)

An article on the dwarf planet Eris, which orbits the Sun beyond Neptune. (Wikipedia)

, which orbits

between 38 AU and 98 AU — it's currently about 96.5 AU away.

Eris is around the same diameter as Pluto, but

significantly more massive. Gonggong(225088) Gonggong

An article on the trans-Neptunian object Gonggong (formerly 2007 OR10), which is probably a dwarf planet. (Wikipedia)

is

another Scattered Disc object we know of.

End of the Sun's Realm

The Sun is constantly blasting out a stream of charged particles, called

plasma, in all directions. The known planets in the inner solar system

are bathed in this solar wind; but it doesn't extend forever. When it comes

up against the interstellar medium (the thin gas between the stars), it

comes to an abrupt end.

The region of space dominated by the solar wind is called the

heliosphere. The point where it collides with the interstellar

medium is called the termination shock; beyond this, the solar wind

ends at the heliopause. This is roughly 100–120

AU from the Sun in the direction of the Sun's motion. Beyond

this, the substance of space is the interstellar

medium, the very thin gas between the stars.

Even this far out, though, we have barely scratched the surface of the

real solar system. There is still a vast realm of space in

which objects are gravitationally bound to, and orbiting, the Sun.

Far, Far Out!

In January 2018, astronomers discovered a new object orbiting the Sun,

designated 2018 AG372018 AG37

An article on the trans-Neptunian object 2018 AG37, nicknamed "FarFarOut". Discovered in January 2018, its distance was confirmed in February 2021 to be 132 AU, making it the farthest known natural object in our solar system. (Wikipedia)

,

and nicknamed "FarFarOut". At its current

distance of over 132 AU from the Sun, this is the farthest known natural

object in our solar system, and so represents the limit of our ability

to explore the solar system with telescopes. (The previous record holder

was 2018 VG182018 VG18

An article on the trans-Neptunian object 2018 VG18, nicknamed "Farout". Discovered in November 2018, it was at the time the farthest known natural object in our solar system. (Wikipedia)

,

nicknamed "Farout", at 123.5 AU.)

In many ways, though, FarFarOut isn't really so far out. Its current

distance is farther than any other natural object we've observed,

but its orbit lies between around 27 AU and 145 AU from the Sun —

in other words, at the inner part of it's orbit, it's closer to the Sun than

Neptune. Its highly-elliptical orbit means

that in the most distant part of its orbit, where it spends most of its time,

it's farther out than anything else we've seen through our telescopes;

but even at this huge distance, it's still not the farthest thing

we know about.

Explored Space

Given the immensity of the solar system, it's strange that the farthest

known object in it should be human-made.

Actual human space exploration hasn't got very far. We've been

to the Moon, which took the Apollo 13 astronauts 400,171 km from the Earth.

This is the farthest that any human has ever travelled, but it's a tiny

distance in solar system terms — just 0.0027 AU, a tenth of a

thousandth of the distance to Neptune. And with the ending of the Apollo

era, we've drawn back even farther. Since 1972, the farthest

any human has been from Earth is 609 km (Hubble servicing mission 3A),

about the length of the drive from London to Edinburgh; and

since 2009, just 406 km (the International Space Station). Given that

the Earth is nearly 13,000 km across, this is really just skimming the

atmosphere.

Arrokoth, by New Horizons

We've done a

lot more with unmanned exploration. We've sent probes to

the Sun — several are studying it right now — and

all the planets from Mercury to Saturn; Uranus and Neptune were visited in

flyby by Voyager 2; and the dwarf planet Pluto was visited by New Horizons

in 2015. Then on 1 January, 2019, New Horizons flew by a small Kuiper

belt object,

Arrokoth(486958) Arrokoth

An article on the Kuiper belt object Arrokoth, provisional designation 2014 MU69, which was visited and photographed by the New Horizons probe in January, 2019. (Wikipedia)

(formerly 2014

MU

69).

This gives New Horizons the clear record for photographic exploration,

having successfully sent back pictures of Arrokoth from a

distance of 43.4 AU from the Sun. (The famous

Pale Blue DotA Pale Blue Dot

An article from the Planetary Society on the Pale Blue Dot picture, the most distant picture ever taken of the Earth. (Planetary Society)

image

was taken by Voyager 1 when 40.5 AU away, so that record has now been

beaten.) However, New Horizons is far from being the winner in overall

exploration.

The Pioneer 10 and 11 probes have achieved amazing distances from earth,

at over 120 AU and 100 AU respectively; but they haven't been doing real

science for a long time. The clear winners are the Voyager 1 and 2 probes.

Launched in 1977, both of these probes are still doing

original scienceIn the emptiness of space, Voyager 1 detects plasma hum

An article about the detection by Voyager 1 of a hum in the interstellar plasma. Published on May 10, 2021. (Phys.Org)

, and they

are speeding away from the Earth. Voyager 2 is

currently 142.5 AU

away from the Sun, and Voyager 1 is

170.0 AU away; making it not only the

farthest space probe, functioning or not, but in fact the farthest known

object in the solar system. Voyager 1 is so far that a radio signal takes

23.6 hours to reach it from

the Sun — and of course it takes the same again for a reply to come back.

Travelling at 17.0 km/s, Voyager 1

is also the fastest probe

leaving the solar system. Its speed equates to about 17,600

years to travel one light year, so making the distance to Proxima Centauri

(if it was heading in that direction; it's not) would have taken over

75 thousand years. Of course it will have run out of power long before

then; in fact, it's expected to shut down around the year 2025.

So we can claim to have explored our solar system — in the most

minimal way — out to 170 AU. But

this is still just

a tiny drop in a very big ocean. Even though we don't know of any specific

object farther out, there's a lot of space there, and it almost certainly

isn't empty.

Out Into the Dark

Sedna90377 Sedna

An article on the trans-Neptunian object Sedna, which orbits the Sun far beyond Neptune. (Wikipedia)

is currently about 86 AU from the

Sun, but its 11,400-year orbit carries it from 76 AU to 936 AU. The only

reason we know about it is because it is currently in a part of its

orbit close to the Sun. An object like Sedna spends relatively little

time in this part of its orbit, which means that there are very probably

a lot more objects like Sedna; most of them will be much farther from the

Sun, and some of them may be much larger than Sedna.

A recent candidate is Planet 9Planet Nine

An article on Planet Nine, a hypothetical large planet in the outer region of the Solar System. (Wikipedia)

,

a hypothetical planet

which may orbit far beyond Neptune. The Planet 9 hypothesis was

created to explain the eccentric orbits of some of the dwarf planets; so

far, there is no direct evidence for Planet 9, and other explanations are

possible. But it's certainly an exciting possibility.

If it exists, Planet 9 may have a highly elliptical orbit, possibly

coming as close as 200 AU from the Sun (over 6 times farther

than Neptune), and moving up to 1,200 AU out. It may be between

25,000 and 50,000 km in diameter, 2-4 times bigger than the Earth, and

maybe 10 times heavier.

You can join in the search for Planet 9, and other outer solar system

objects. The

Backyard Worlds: Planet 9Planet 9

A citizen science project to find Planet 9, and other new objects at the edges of our solar system. You can join in to search for distant solar system objects in telescope images. (Backyard Worlds)

project

is a citizen science project where you can search telescope images for

objects like Planet 9. This is not only a great way to make a real contribution

to astronomy — and potentially become the discoverer of Planet

9 — but looking at the images will give you an idea of why finding

these objects is so hard, as you scour very noisy images for very faint

moving specs.

If Planet 9 exists, and orbits out to 1,200 AU, this is still just over

2% of the way out to the edge of the solar system. There's no way to

know how many other objects there

may be orbiting beyond that distance. Given the vast amount of space out

there, though, we can speculate that there may be many. But at present,

this is an immense, and completely unexplored, volume of space.

The Final Belt

Although we can't detect anything in the outer reaches of the solar

system, there is circumstantial evidence for certain things out there.

Comets which drop into the inner solar system must come from somewhere,

and analysis of their orbits suggests that there is a vast reservoir

of icy objects at the outer edges of the solar system.

This immense cloud of proto-comets is called

the Oort cloudOort cloud

An article on the Oort cloud, a hypothetical belt of icy objects orbiting at the edge of our solar system. (Wikipedia)

, after Jan Oort,

one of the astronomers who worked on the hypothesis.

The Oort cloud objects are orbiting the Sun, being gravitationally

bound to it, in stable orbits — or at least partially stable. Towards

the outer reaches in particular orbits become increasingly tenuous and easily

disturbed, sending one of these objects out of its orbit. Sometimes

these crash down into the inner solar system, and become visible comets.

Farther out, nothing can be in a stable orbit around the Sun; so the Oort

cloud is generally reckoned to be the final frontier of the solar system.

The actual boundaries of the cloud are very hard to even estimate.

The distance to the inner edge of the cloud is estimated at between

2,000 and 5,000 AU. The outer edge may be 50,000 AU (0.8 light years) away,

or even as far as 100,000 AU (1.6 light years); sometimes estimates as

high as 200,000 AU (3.2 light years) are given, but this runs into

trouble with the Hill sphere, as explained below.

So the Oort cloud may cover 90% or more of the width of the solar

system, and yet we really know nothing about it, or anything else in

that region of space — we only have evidence of its

existence from visiting comets. Still, it is fairly certain that the

cloud exists, and that there are large objects in it whose gravity knocks

comets down into the inner solar system once in a while. Beyond that,

it's a mystery.

The Limit of the Sun's Grasp

The absolute limit of the solar system is the distance at which the Sun's

gravity can no longer hold orbiting objects against the gravity of other,

nearby stars. This distance is called the Sun's

Hill sphereHill sphere

An article on the Hill sphere, the limit of an object's gravitational attraction for orbiting objects. (Wikipedia)

. Beyond this, nothing

can be in a stable orbit around the Sun.

Unfortunately, computing this distance is not simple, as it depends on

the characteristics of the "other nearby stars", and they're all moving.

However, a practical estimate for it is probably somewhere around two light

years, or 125,000 AU.

Even this is only a rough guide, though, as orbits near the edge of

the Hill Sphere become increasingly fragile; the likelihood is that nothing

can really be in a long-term stable orbit anywhere close to the edge of

the Hill sphere. So there's no realistic way to set an exact limit on

the reach of the Sun's gravitational dominance — but there certainly is

a limit.

The Hill sphere is the ultimate outer limit on the Oort cloud.

Once past the Oort cloud, we have finally left the solar system, and have

ventured out into interstellar space. (Voyager 1 will be here in around

35 thousand years.) The

next significant thing to see will be another solar system.

And Beyond...

The nearest star to our own solar system is Alpha Centauri. However,

it's not quite that simple, as Alpha Centauri is now known to be a 3-star

system.

The two main members of the system, Alpha Centauri A and B, are quite

large stars and orbit each other relatively closely, with the centre of

the system being around 4.37 light years from the Sun.

The third star, Proxima Centauri, is a small red dwarf, orbiting A and

B in a very elliptical orbit which takes half a million years. Since it

is currently on the side of its orbit towards us, Proxima is currently

the closest star to us, at a distance of 4.25 light years — or

around 268,400 AU.

And beyond this are billions more stars. Barnard's Star,

a very small red dwarf, is about 6.0 light years away; Wolf 359, another red

dwarf, is about 7.9 light years; Lalande 21185, yet another red dwarf, is

about 8.3 light years; and Sirius, a massive binary star and the

brightest star in our sky (after the Sun), is about 8.6 light years.

All of these, of course, are just a handful among the hundreds of billions

of stars in the Milky Way galaxy. This is a disc-like aggregation of stars,

about 100,000 light years across. The Milky Way itself is just part of the

Local Group of galaxies, which in turn is part of the Virgo Supercluster,

a collection of galaxies 110 million light years across. This in turn

is just one of about 10 million superclusters in the

observable universeObservable universe

An article on the observable universe, the region of spacetime which it is possible for us to observe. (Wikipedia)

, which is

around 93 billion light years across, and contains at

least 2 trillion galaxies.

And Beyond... ?

It's impossible to say what lies beyond the observable universe

(by definition), but it's not likely that the physical universe stops there.

It probably goes on for quite a distance; but whether infinitely far,

or for a finite distance, is unknown. There may even be other universes

beyond our own, but as of now, that's basically speculation.

Solar System Summary

This table lists some of the main landmarks described above. Bear

in mind that a lot of these distances are highly speculative; but still,

this should give you an overall idea of the scale of things.

The third column shows how quickly Voyager 1 could make the journey, travelling

in a hypothetical straight-line path from the Sun. This is not the actual route

flown by Voyager 1, and it was travelling more slowly at first, so the numbers

do not match up to the actual arrival dates; but this might give you an idea

of how quickly a spacecraft could theoretically get there. (Voyager 1 is the

fastest man-made object leaving the solar system.)

The last column shows how many times farther the given landmark is from

the Earth than the Moon is. Given that the Moon is the greatest distance

humans have ever travelled, this gives some idea of how hard it would be to

reach a particular place.

| Landmark |

Distance from Sun |

Voyager 1 from Sun |

Times the Moon |

| (AU) |

(miles) |

(straight-line time) |

| Mercury (the innermost planet) |

0.390 |

36.3 million |

0.11 years |

237 |

| Earth |

1.00 |

93.0 million |

0.28 years |

0.00 |

| Pluto (closest, in 1989) |

29.6 |

2,750 million |

8.3 years |

11,100 |

| Neptune (the outermost known planet) |

29.9 |

2,780 million |

8.3 years |

11,200 |

| Pluto (farthest, in 2114) |

49.3 |

4.58 billion |

14 years |

18,800 |

| Kuiper Belt outer limit |

50.0 |

4.65 billion |

14 years |

19,000 |

| Eris (now) |

95.8 |

8.91 billion |

27 years |

36,800 |

| Heliopause (roughly) |

121 |

11.2 billion |

34 years |

46,600 |

| Voyager 1 |

170 |

15.8 billion |

47 years |

65,700 |

| Sedna (orbit limit) |

925 |

86.0 billion |

260 years |

359,000 |

| Planet 9 (possible) |

1,120 |

104 billion |

310 years |

435,000 |

| Oort cloud start |

2,000 – 5,000 |

190 billion – 460 billion |

560 – 1,400 years |

780,000 – 1,900,000 |

... the vast majority of the solar system

is completely unknown space ...

|

| Edge of the Solar System |

50,000 – 100,000 |

4.6 trillion – 9.3 trillion |

14,000 – 28,000 years |

19 million – 39 million |

| Proxima Centauri |

269,000 |

25.0 trillion |

75,000 years |

104 million |